-

-

-

Sagesse 1-5, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

L’Amour, 1999, oil on canvas, 123x400cm

Sculptures: Lawrence McLaughlin

-

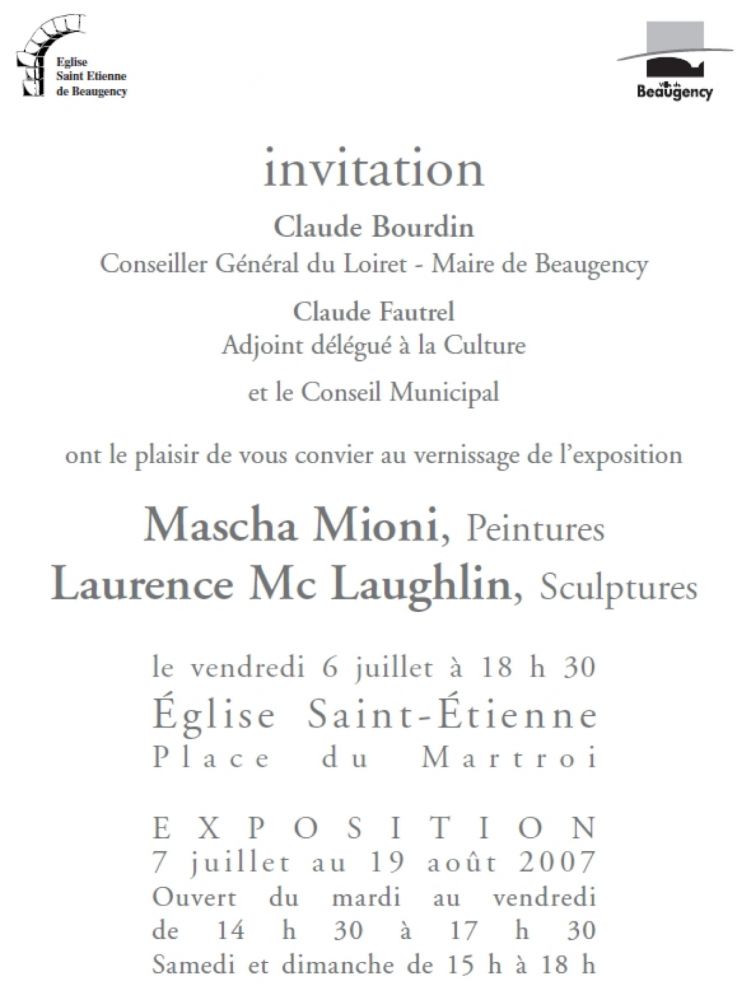

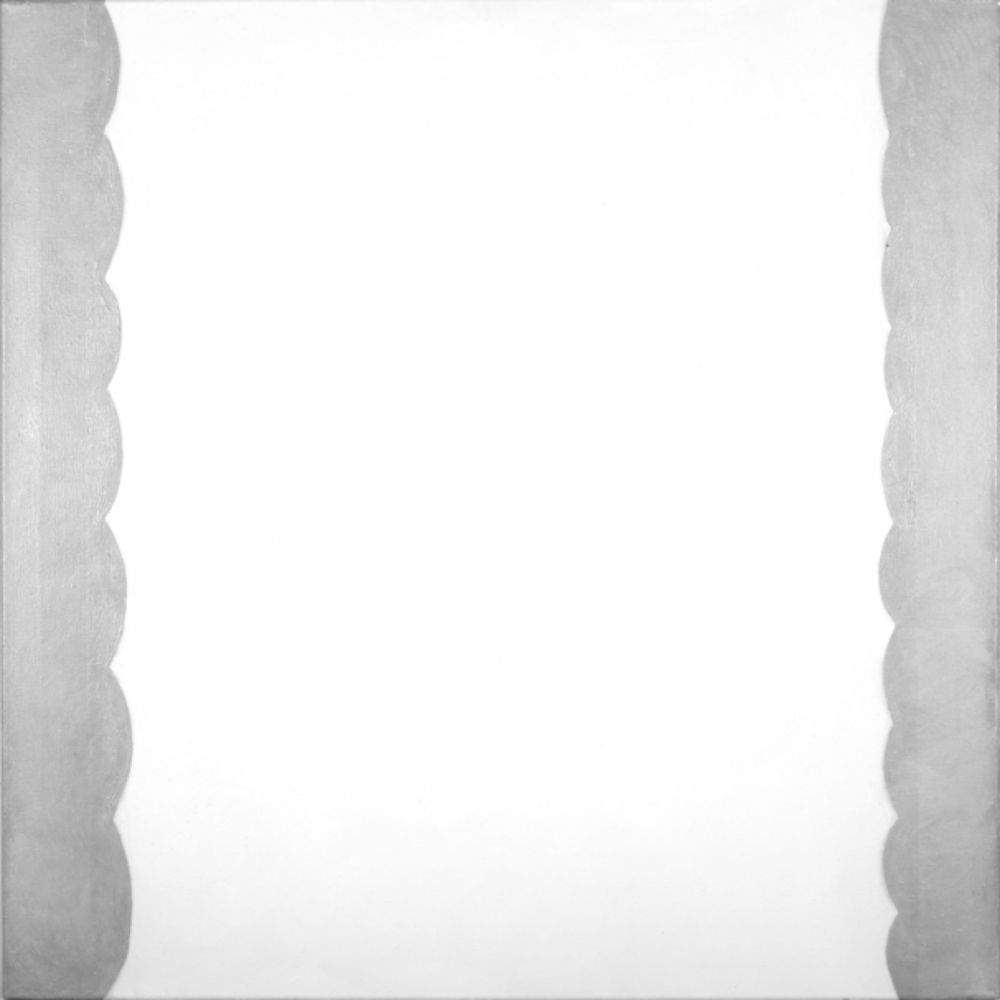

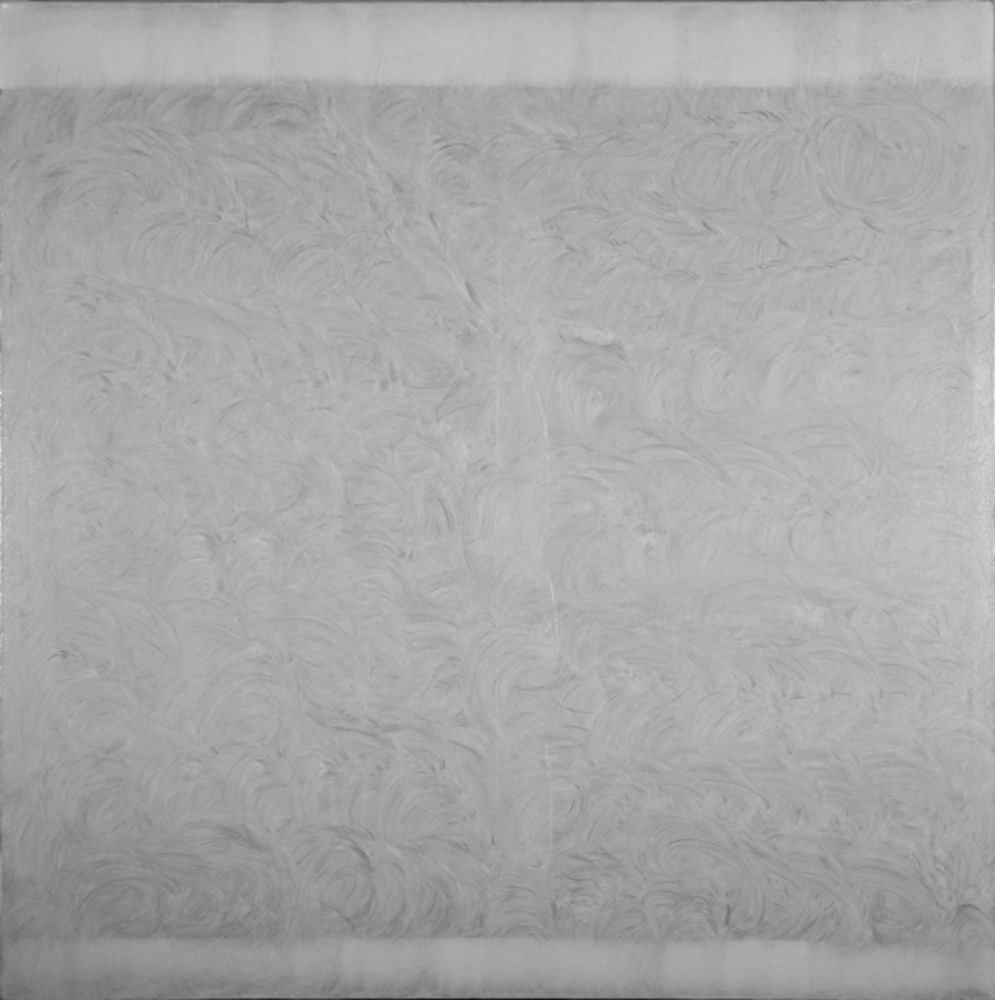

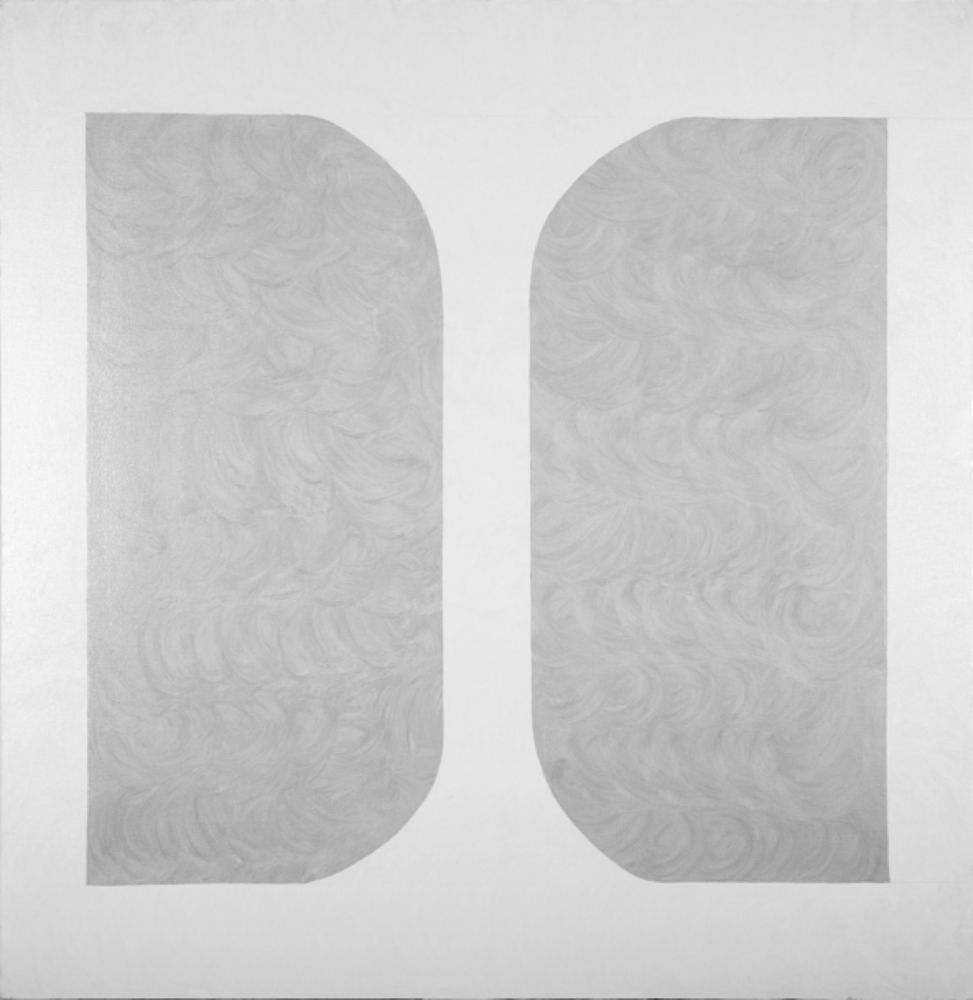

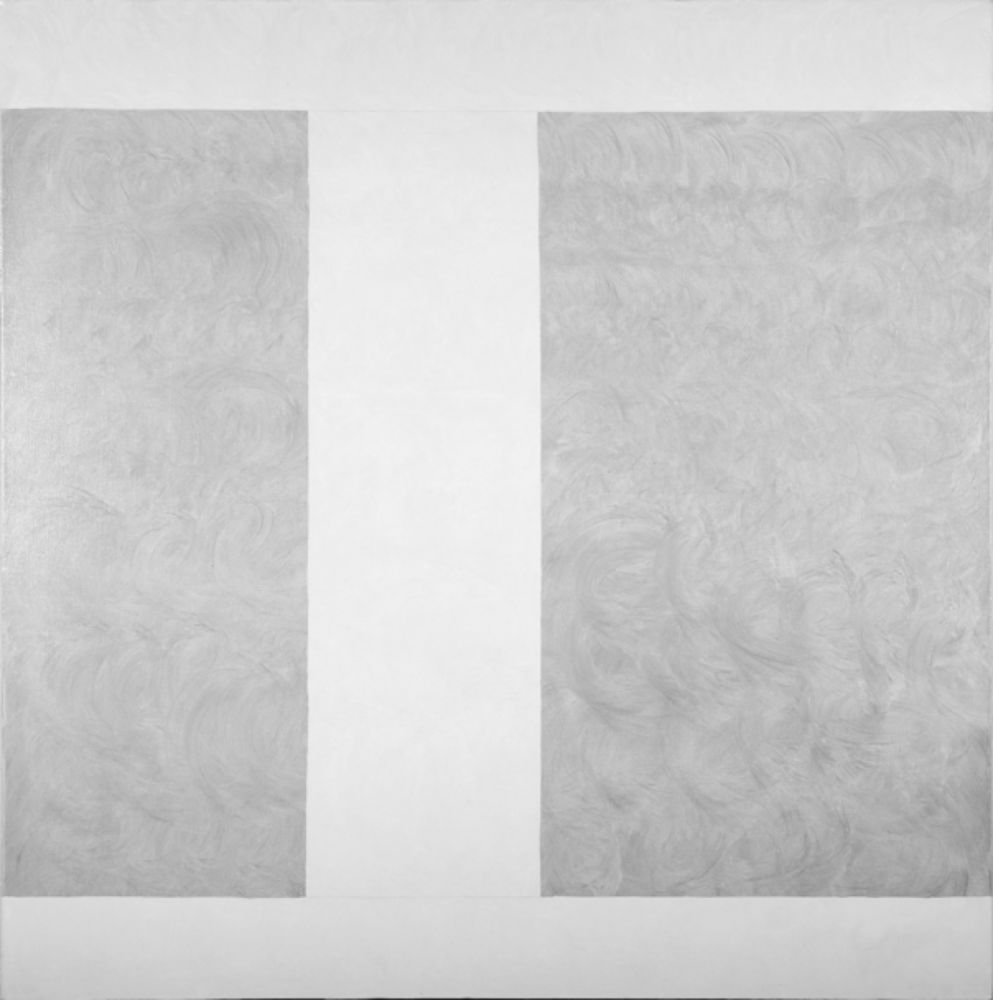

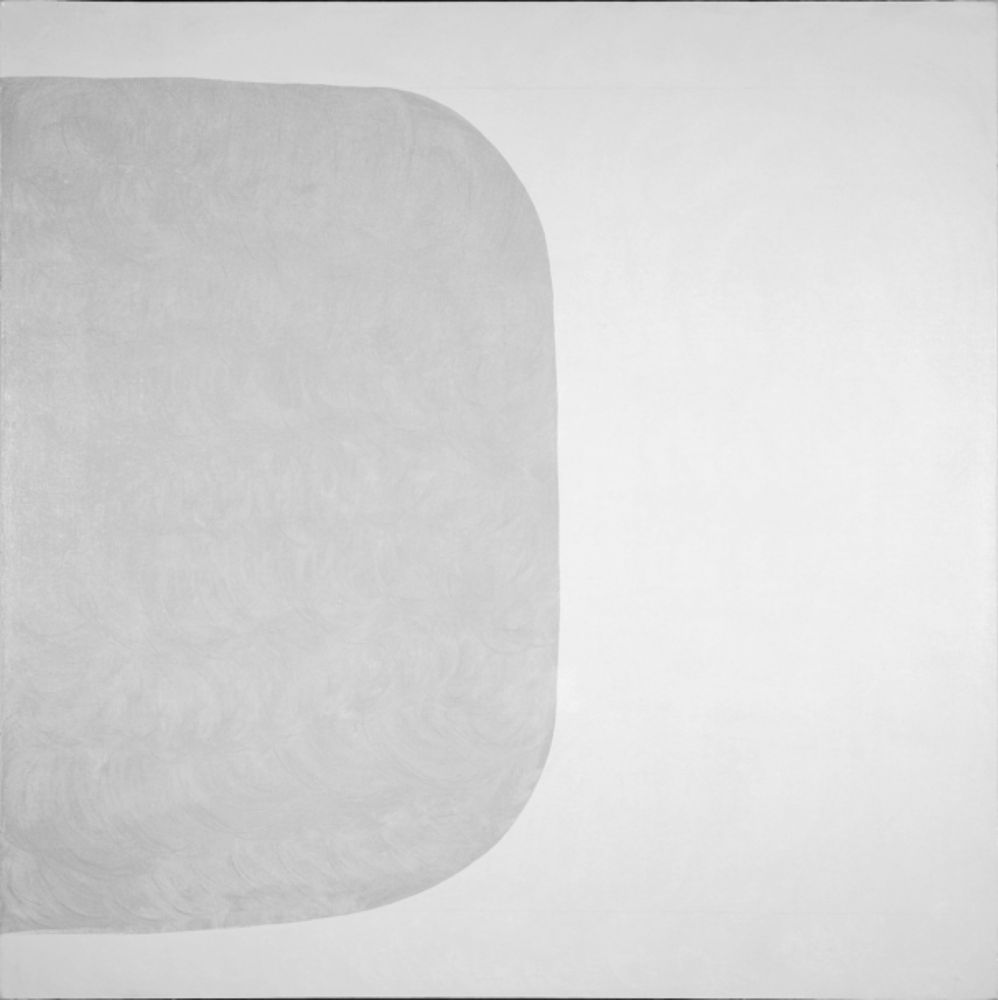

Sagesse 1, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

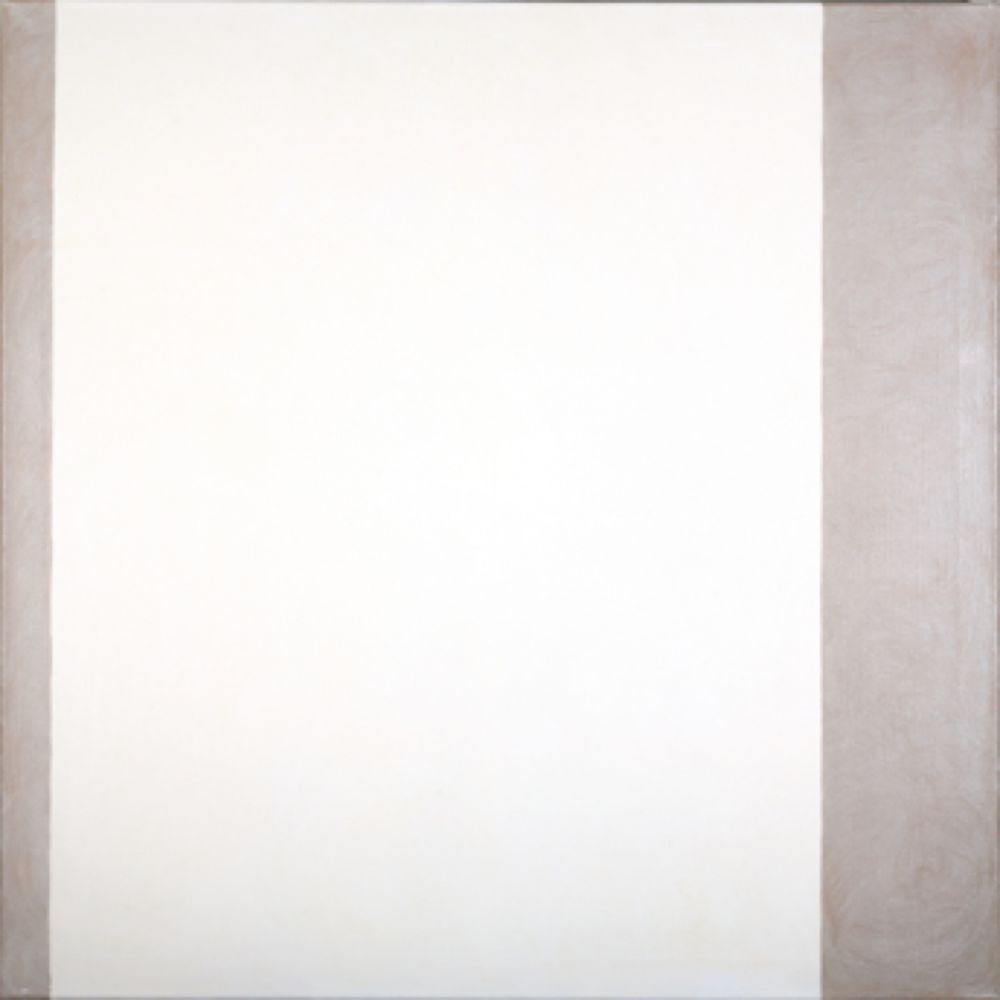

Sagesse 2, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

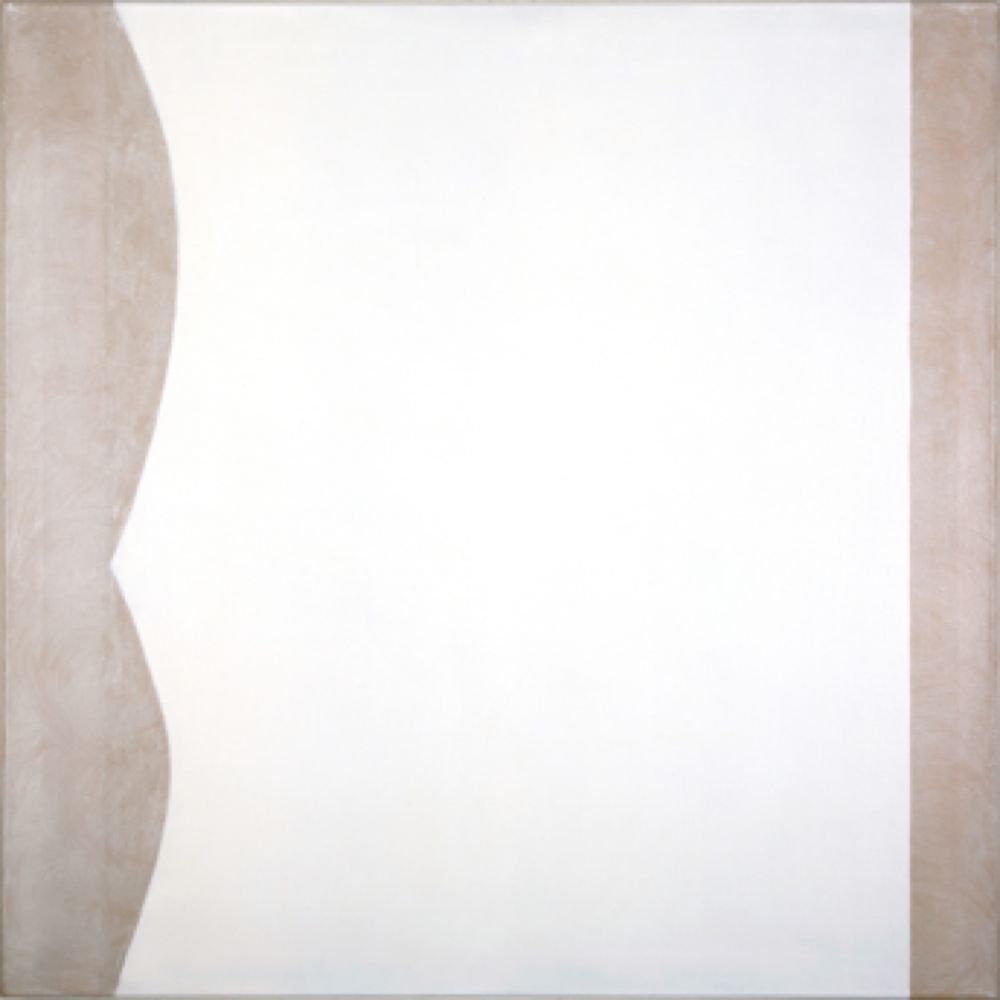

Sagesse 3, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

Sagesse 4, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

Sagesse 5, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

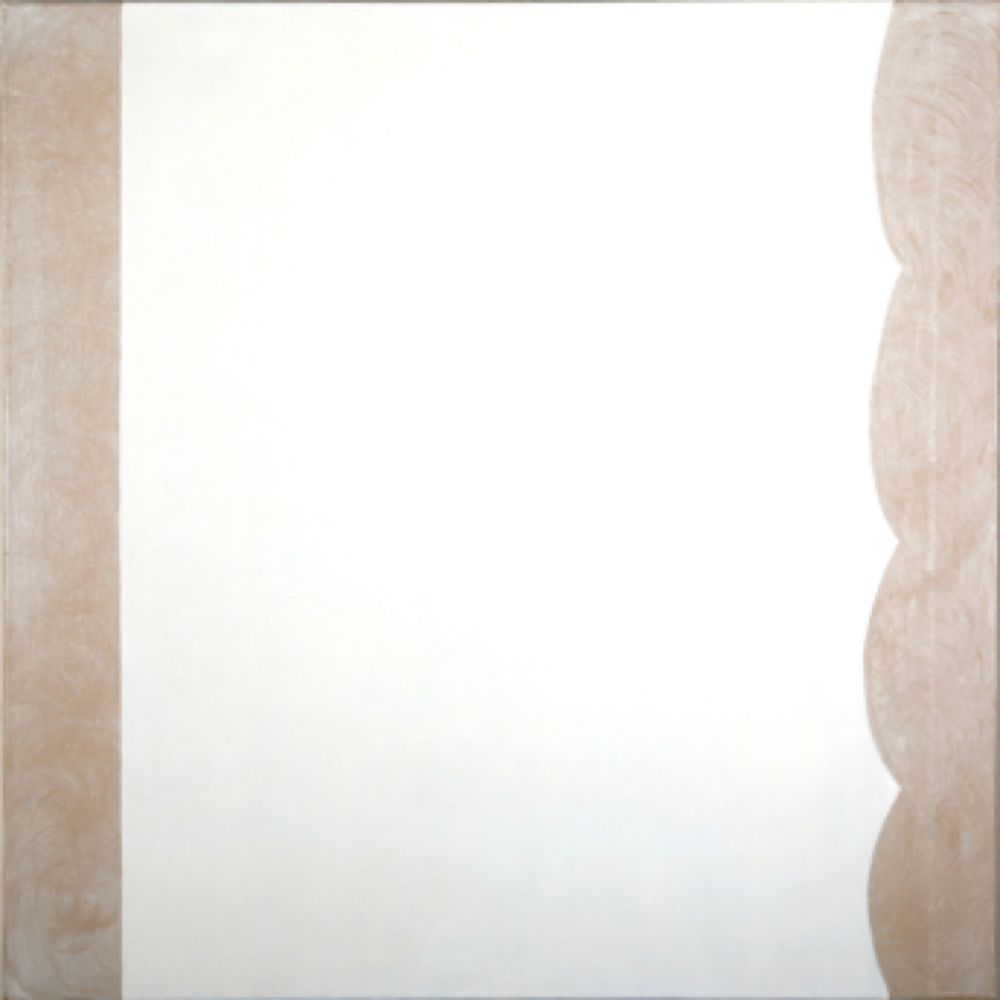

Jeanne d’Arc, 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

La Lumière, 2000, oil on canvas, 500x208cm

Sculptures Lawrence McLaughlin

-

Loiret 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

La Lumière, 2000, oil on canvas, 500x208cm

Sculpture Lawrence McLaughlin

-

L’Amour 1999, oil on canvas, 123x400cm

Sagesse 5, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

Sculptures Lawrence McLaughlin

-

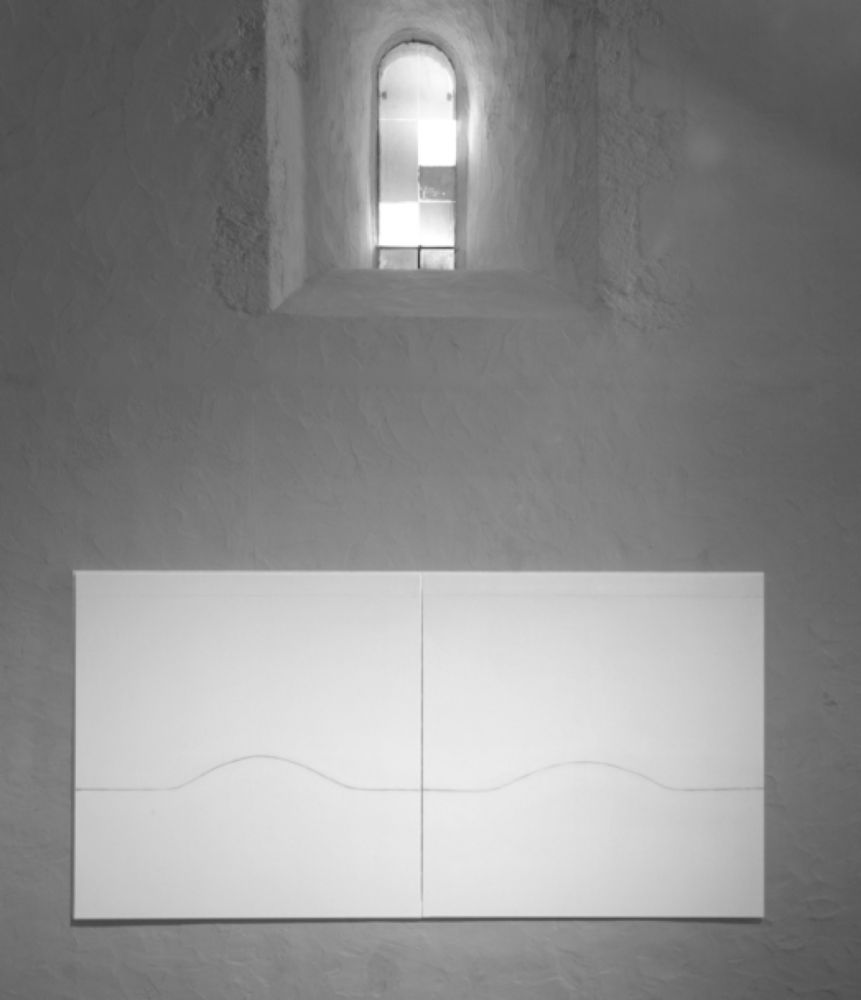

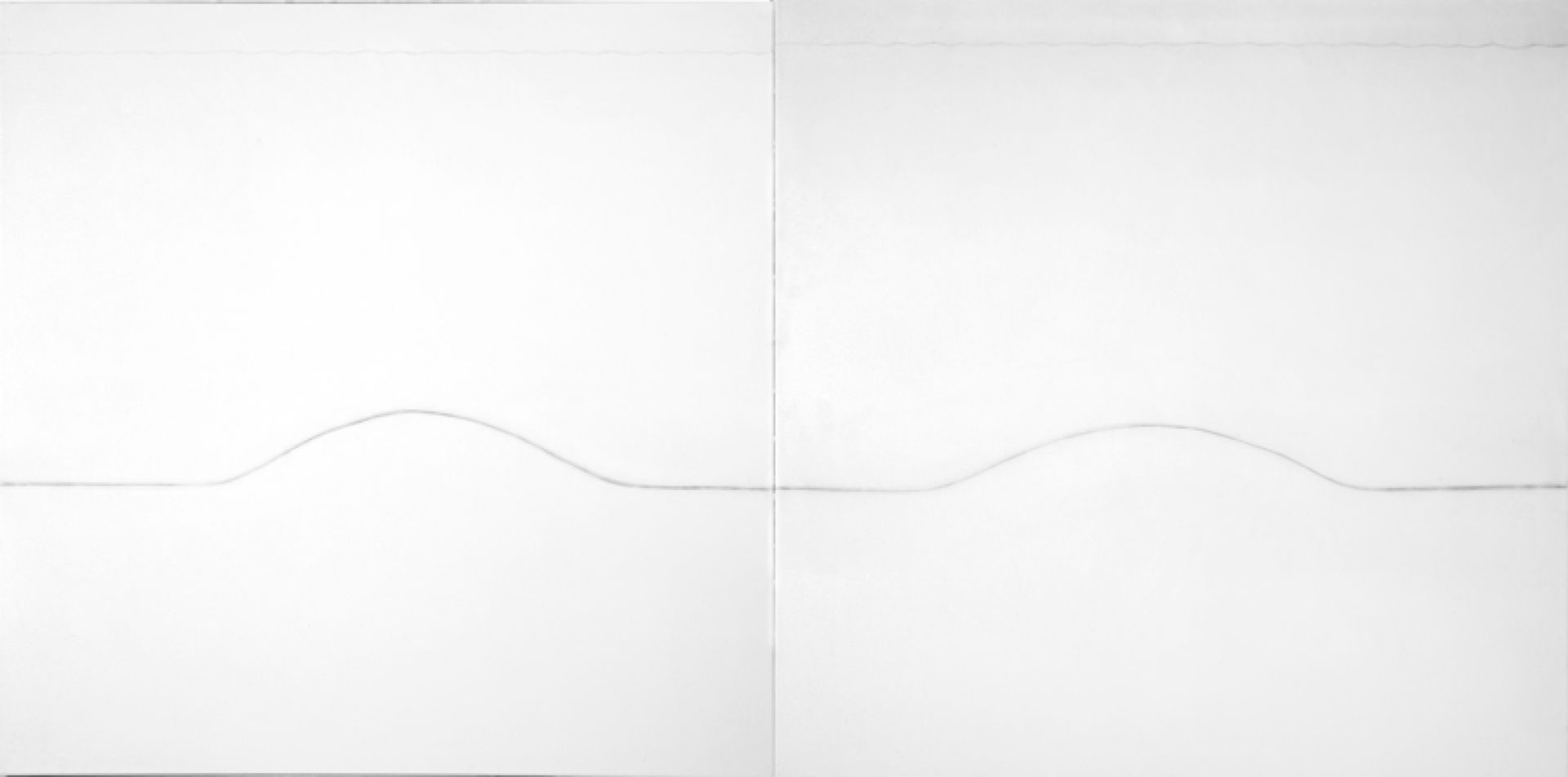

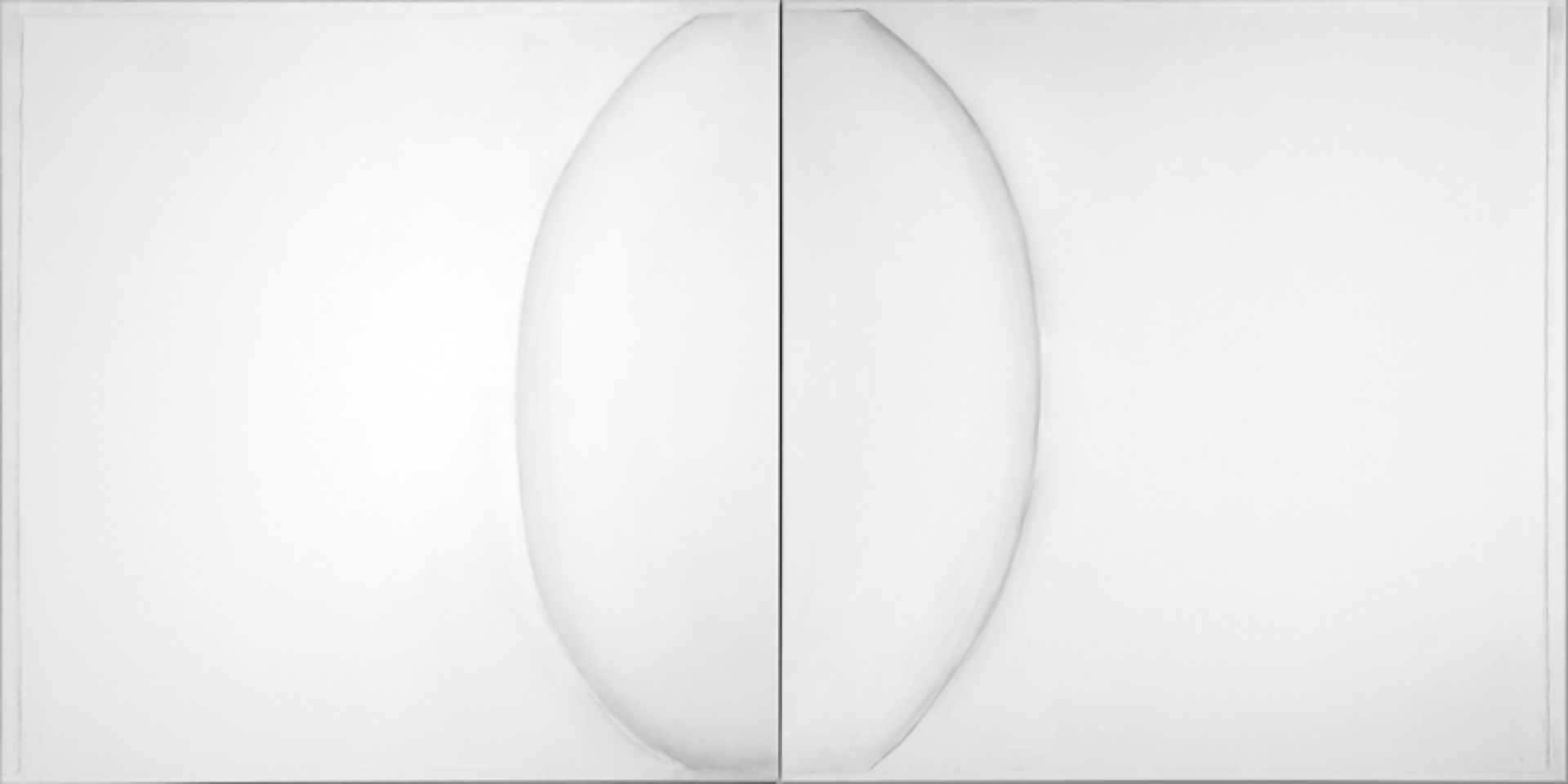

Le Chemin, 2006, oil on canvas, 2x100x100cm

-

Le Chemin, 2006, oil on canvas, 2x100x100cm

-

Le Chemin, 2006, oil on canvas, 2x100x100cm

Sculptures Lawrence McLaughlin

-

L’Union, 2006/7, oil on canvas, 2x100x100cm

-

La Lumière, 2000, oil on canvas, 500x208cm

Loiret 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

Beaugency, 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

St. Etienne 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

Sculpture Lawrence McLaughlin

-

Jeanne d’Arc, 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

Loiret 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

Beaugency, 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

St. Etienne 2007, oil on canvas, 100x100cm

-

2007 Beaugency/F

Mascha Mionis paintings and Lawrence McLaughlins sculptures in the museums-church Saint-Etienne, Beaugency, France

Encounter

Mascha Mioni’s paintings and Lawrence McLaughlin’s sculptures, which enter into a beautiful dialogue with one another, were brought together for the first time in 1993 in Carolina Bearth’s gallery in Chur/Switzerland. Two years later Mascha and Lawrence met for the first time personally and a fruitful and smooth cooperation began. This resulted in joint exhibitions in 1998 and 1999 in the gallery In der Loft, Dietikon/Zurich, in 2003 in the Atelierhaus Altstadstr. In Meggen/Lucerne and in 2007 in the Eglise St. Etienne, Beaugency/France.

Bruno Lavillatte, Writer and Art-Critic on the exhibition

A Space Place

Obviously, there are walls. And whiteness. White spaces like banks of snow. The treasure is this small church - Saint Etienne de Beaugency, where emanations from our souls reach all the way down to our feet. Emanations that take us, surround us, embrace us in perfect accord. Mascha Mioni and Lawrence McLaughlin have become part of that embrace. Their work occupies the space together, merging without canceling the artists' personal individuality. But ultimately, the exhibition is a triptych. We know two of the artists; the third is four centuries old, speaking only through the interposed stones and the walls, assembled as if to reach the sky, via the force of the spirit coalesced with the material.

What Mascha Mioni paints is a transparency - precisely, a burst of the soul within our reach. A burst that exposes our humanity to be discovered. Something we never see, but keep concealed within us. Olivier Debré revealed the Loire, its secrecy, the light caressing whatever dropped from the blue sky to the wet gray losing itself on the banks. The large stones and boulders he applied as he wished on the canvas. Mascha Mioni reveals as well: she peals off the obvious reality, the pulpy flesh, the cushy excess. Anything massive, anything heavy - she removes it. McLaughlin, too, dispenses with excess, eliminating unnecessary appendages that distract from the core: no hands, no feet. The head is gone as well. There is always the strong base. It is the essential core figure that will stay infinitely - standing upright, always upright.

The unity of the two artists is expressed in a common peculiarity: they both work with what I will call, from now on, a 'release.' For Mascha Mioni and Lawrence McLaughlin, surplus is a burden. They want only to see the purest of simplicities. In that, their work is connected with an archaeology of form; each one individually 'releases' the inessential and seeks what remains of pure form. In the sculpture of Lawrence McLaughlin, as in Mascha Mioni's painting, is an initial form, uncluttered of obstruction. For these artists, to envision the foundation, the source, the origin, there can be no impediments. Because their work interplays so well together, we can see it as bare, unadorned forms, without even considering the material.

Of course, we can speak about purity, transparency, limpidity, simplicity. We can, and so I did at the beginning of this text. In fact, I think the reality is something else. It is not so simple. In general, abstraction is an attempt to “steal” information, in order to uncover or reveal the original form, the source, the mother form, which will always play hide and seek with our eye. Braque makes everything flat. Picasso puts everything to the side. Miro makes splashes and unwinds a few strings. Kandinsky mixes everything (up). Giotto lengthens his cypress trees, narrows the Tuscan roads. Piero della Francesca pushes angles to the limits of perspective. The light on the woman's face in Tintoretto's painting 'Christ before Pilate' comes from somewhere beyond. Chardin composes his still lives as he wishes, more alive than ever. All of this is to say, any art is an abstraction of reality; any art is innately abstract. There are things missing, arranged, taken out or recomposed. Cleaned. Of course every realistic work is not copied from reality. That would be photography, and if that were the case, why would there be photography?

My point: the unity of this exhibition - its coherence - is the artists' disregard for the superfluous. And we realize it. We get it, this something, without it being a formal concept. I want to make a comparison: the Cross does not need Christ to be the Cross. The body of Christ is so beautiful - particularly in the Renaissance period, that it is paradoxically inessential, extraneous. It is always on the Cross. The body is so present, that it does not have to appear. Therefore, any cross, becomes the Cross. That is the force of the symbol: it is a form that only needs itself to exist and to have meaning.

All things considered, the works of Mascha Mioni and Lawrence McLaughlin share this same enriched quality. They are eminently symbolic, not strictly for what is represented, but for what was removed. The power of their work comes from this 'release,' to more effectively express the essential form. Since medieval times, people speak about the 'True Cross', saying nothing, nothing of Christ. He is not physically associated with it. The aesthetic sensations we feel as we enter this church are of the same order: born from a perception of all that has been removed, awakening to all that needn't remain intact. Everything that was un-nailed. Everything that was taken away. As I visited the Maeght Foundation this year, I was seized by a curious feeling on the back terrace. The base of Giacometti's sculpture is overall the same as McLaughlin's: strong, massive, unique. And yet, there was a fundamental difference. What Giacommeti keeps, McLaughlin takes away. Cancels. This sense of what is released is what grounds the aesthetic feeling. We begin to see that McLaughlin's vision of the world is a process of reduction, one that doesn't reduce the essence of the world, but emphasizes it.

For Mascha Mioni it is the same. There could be splashes, drips, obviously visible brush strokes, exuberant color as in many of her most beautiful canvases. But here, no. In this particular space, addition and surplus do not have a place. A smooth rendering has occurred, enabling her to give us the essential form, meaning that the extent of the space and the most appropriate color for this space become white, or hints of white or gray, this being the ultimate sign of what has been extracted and discarded.

With Lawrence McLaughlin, it is never obvious. He needs materials, and that is his paradox: having released the inessential, it is necessary materially to present the essential. He rebuilds his own treasures, giving them a density that does not distort the essential form. Everything works together, enabling the form to be truly visible. Cement, metal, plaster. They are all essential to make the work possible. Necessary to present a form that otherwise would not hold itself, to embrace itself, to hold it tight and keep it close. It is at this point that this form looks at us, that its light passes through and spreads into the space. And it becomes the eye that sees and understands, like the birth of the world, a kind of absolute beginning. I invite you to pass behind the sculptures. It is worth the detour to find out how the form uniquely confronts and sees the world. By removing unnecessary materials, the artist has made it possible for the new material to take shape, a material manufactured from the original matrix, but refocused. One might think some kind of enigma has come to life. The original light emerges from this amalgam of cement, resin, plaster and metal, as if from the beginning of time. McLaughlin's sculptures seem to spring from another era. They have existed for 21,000 years, contemporaries of the Venus of Lespugue whose one foot takes root in the history of mankind, whose breasts and hips show the future of humanity and man's spiritual future, seeking release, and opening his desire to see and understand what exists beyond the mountains and under the eternal ice.

With Mascha Mioni, spaces seem to come to rest, to open up but to get close as well, to give life to and to cleanse the wounds of a world she is no longer considering. Her work is the mirror to McLaughlin's depiction of new beginnings where everything is cleansed. A resurrection! A moment when everything becomes possible and all seems to open up. And so, that too is what the space in Mioni's paintings is - an open space - without limits. McLaughlin's works contrive their own limitless ascent towards the sky. If he allowed it, they wouldn't stop, if he didn't put a limit on what you can see.

Obviously there are white walls and spaces as white as snow banks. Obviously, it couldn't be otherwise in this little church of Saint Etienne, stripped of everything recalling a suspect world. A world where one must always be on the look-out for any glimpse or sign that allows us to see another better world. The unity between this space and the artists is unmatched. It seems engraved in the history of this exhibition, a history that we may not really understand. This church, after 17 centuries, is the symbol of a 'form of archaeology,' which in Caphargamala in 415, led Lucien the priest to discover Saint Etienne’s body, the first martyr of the Church. The body had been lost, buried beneath piles of stone. With the presence of Mascha Mioni and Lawrence McLaughlin, this church is not a simple exhibition space, it is a way to help us understand that we, believers and non-believers, must commit to the indispensable truth that it is always possible to see with our eyes half closed, ‘the open Heavens that rain on our feet and awaken our Souls’. Without doubt, such is the concept of this space.

B. L. July 26, 2007